Part 1: Live Poultry, Fresh Killed

It was one of those things you do because you can: I gave my (first) master’s thesis defense wearing a lurid red Live Poultry Fresh Killed T-shirt under a serious gray suit. During infrequent moments when the T-shirt was evident under my open suit jacket, defense committee members would firmly clasp a finger or two across across their faces in failed attempts to stifle laugher. At least, I THINK that’s what they were laughing at. The topic of my defense – the manufacture and efficacy of vaccines to prevent pandemic avian flu – was not, in and of itself, especially mirthful.

I became interested in the topic of flu vaccine for two reasons. The first was that, some years prior to my defense, I was stricken with the worst flu of my life in spite of having dutifully received my flu vaccine at the start of the season. That year, the winter of 2000, a particularly nasty strain of flu raged through North America with the pugnacious impunity of a nuclear-armed megalomaniac with a twitter account. I was then in my early 20s. Normally, I was healthy enough to pursue multiple martial arts. The week of the G.I. puke, as it was colloquially known, I had a fever of over 101F for five days straight. I did my best to stay hydrated, knowing that any minute my innate immune system would kick into high gear and punch the viral Nazis attempting to take over my respiratory system right in the face.1 However, on the fifth day, while trying to lower my core body temperature in the shower, I nearly passed out. Less than an hour later, swathed in a ski jacket and knit cap, I was shivering my way down towards the student infirmary. In my febrile haze, I remember noting what a beautiful, brilliantly warm January day it was in Northern California. Also, that I wanted to die. I plunked myself down in a waiting area whose walls matched the minty pallor of my face and waited for somebody, anybody, to bring me a bag of IV fluids.

Fast-forward to 2005-6 and reason #2: A deadly new strain of avian influenza was casting a chilly shadow across the planet. I was just completing my degree in biotechnology at the University of Rhode Island. It seemed like the ideal time to get people to discuss how, when the time came, we would effectively punch a pandemic bird flu in the face for real.

The first step in that conversation involved me understanding how the flu itself functions: how it evolves, every year, like a perpetual-motion fever-machine. The second step was studying how we currently attempt to derail the flu machine, with varying degrees of success. Finally, I would come to understand and explain, in general terms, how we could all get ahead and stay ahead of the bird flu – in time to prevent a global catastrophe.

Part 2: Roombas and Killer Rabbits

12 years and multiple degrees later, the best metaphor I have for influenza remains the one I used while standing in front of my thesis committee in a gray suit and chicken-themed T-shirt. To put it plainly: the flu is like a killer dust bunny. It blows all over the world picking up pieces of other flu viruses lurking in all the foulest corners of the earth: from chicken coops to pigpens, ICUs and animal slaughterhouses to big-city slums. As a result, it looks like one thing one week, and another thing the next. And how do we fight dust bunnies in the modern age? With a Roomba2 of course!3

As silly as it is, the Roomba metaphor helps me explain to my patients why they should get the flu vaccine every year even though it does not prevent the flu. No one expects a Roomba to clean their entire house from top to bottom, right? That would be awesome, but that’s not the way a Roomba works. All that little machine can do is cut down on the dust and debris in your environment. Similarly, no one should expect a flu vaccine to protect them entirely from the flu. What it’s designed to do is to cut down on how sick the flu can make you. It does this by giving your body the opportunity to learn to fight off a few types of flu.4 If your body accepts that opportunity and subsequently meets one of those flus, you will be in a better position to more effectively punch it in the face.

In practice, this might mean that you get “the flu” – one of those three or four in the vaccine – but show no sign of illness. It could mean that you get the flu, but only get a little sick. It could mean that you get pretty sick, but don’t go to the hospital. It could mean that you go to the hospital, but don’t end up needing to be intubated. It could mean that you end up intubated with a big machine breathing for you, but you live to tell the tale.

Importantly, like buying any consumer product – be it a Roomba or a flak jacket – the flu vaccine isn’t perfect nor should you expect it to be. Unlike most consumer products, for a modest price it can absolutely increase your odds of survival, especially if you are a child, over 65, have asthma or any immunodeficiency, and enjoy breathing oxygen. Like a flak jacket, motorcycle helmet or seatbelt, the flu vaccine is an opportunity to walk away with as much of your health intact as possible, with an added bonus: it helps shield others who might be cruising through flu season without a helmet or a seatbelt on.

To be sure, there are plenty of people who don’t wear helmets or use seatbelts. There are plenty more who don’t get the flu vaccine. I see people who make these decisions in the hospital on a regular basis in various states of not-ok. Right now where I work there are literally hundreds of people suffering from the flu. The vast majority did not get the flu vaccine. However, like me back in 2000, some did get their vaccine on time. As luck would have it, they met one of those nasty flu-bunnies that this year’s vaccine did not prepare their body to fight. A few did meet one of those three. For various reasons, the fight their body put up wasn’t enough to keep them out of the hospital. As I did many years ago, these folks now need a little extra help getting better before they can go home and get on with the rest of their lives.

In both the vaccinated and unvaccinated group, the vast vast majority will get better. However, the vaccinated group will get better faster because while their bodies learn to fight a new kind of flu, they are already protected from three others. The house is cleaner than it would’ve have been otherwise. The vaccinated humans have a leg up in this bunny-battle: one that may be small, or significant, or life-saving, depending on the year, the person, and the strains of flu.

Then, of course, there’s those thousands who won’t get better. Like this poor child here, most will turn out to not have been vaccinated at all.

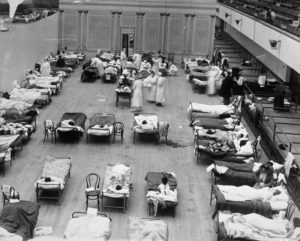

1918 flu epidemic: the Oakland Municipal Auditorium in use as a temporary hospital. | Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Why the unvaccinated fare worse is something I learned about while preparing my thesis in 2005. I learned that it wasn’t the flu virus that killed most people during the 1918 world Spanish flu epidemic: it was the pneumonia they got when they were already down with the flu. Something I wish more people understood is that dodging the flu isn’t just about avoiding a week of fever, vomiting, chills, and generally feeling like you want to die. It’s about cutting down your odds of dying from other things, like pneumonia. And strokes. And heart attacks. Fighting the flu consumes your body’s resources and sets off chains of events that makes other kinds of badness far more likely. In the 12 years since I earned that Master’s degree, it’s become clear that avoidable flu related badness has a big range: far bigger than we understood then and almost certainly far bigger than we understand now. The child above likely perished because he already had asthma. His compromised airways didn’t have the reserve to handle the flu on top of everything else.

Part 3: New Bugs and Old-School Medicine

Few things in life are as simple as getting a shot in the arm to avoid dying a horrible death from a wide variety of preventable diseases. All the stuff that happens BEFORE the shot gets to your arm – what’s in it, where and how it’s made – is bizarrely complicated. This is true thanks, in large part, to our incredibly outdated vaccine manufacturing system.

You see, at the outset of the second world war, in order to prevent a repeat of the 1918 calamity, we started making flu vaccines using what we had available at the time: other animals. We started with ferrets. We quickly found that infecting chicken eggs with the live flu virus worked faster, cheaper and better. We then harvested the infected embryos before the virus completely took over, but not before it had enough time to replicated and allow us to make a successfully strong vaccine.

So – 70 years later, how do we make flu vaccines?

You guessed it: the exact SAME WAY.

To bring this antiquated process to a successful conclusion requires a lot of good timing, good luck, and good-natured hens. This system also requires a minimum of six months of lead time – filled with injecting eggs, then harvesting viruses, then shaking the viruses to death, then purifying and putting the pieces into vaccines, then shipping and distributing them.

Multiple parts of this system make producing a vaccine against bird flu exceedingly difficult. Specifically: chicken embryos die quickly when exposed to a virus especially evolved to kill them. The few embryos that don’t die leave behind very little virus for us to use in our vaccine making process.

Part 4: New-School for Punching Flu in the Face

People ask: What do we need to do to get the flu vaccine to work better? My Answer: a system of vaccine manufacture that is synthetic, real time, dynamic and distributed.

By synthetic, I mean ditching the chicken-and-egg system in favor of the method we use for hepatitis B or HPV. Those two vaccines aren’t made from live viruses: they are genetically engineered to look like the virus we want to punch. Ideally, every year, we would put together gene sequences of all the flu viruses currently in circulation and feed them to yeast. The yeast would multiply and give us pieces of viruses we could use in vaccines.

Doing this in real time would mean that when a new flu shows up in Fiji, vaccine production companies in California would scale up and push vaccines with the relevant virus pieces out the door within weeks. Having this process be dynamic would mean that as cases the first cases of the flu come and go across the country, the vaccine would respond to the change.

Doing this all in a distributed way would mean that vaccines would be produced in every state across the country as they are needed to reflect the viruses that are showing up there as they show up.5

That kind of flexibility in public health response does not exist at any substantial level in today’s society: but it could, and it should, and it must if we are to avoid the global pandemic we all feared more than a decade ago.

That was my thesis in an eggshell.

Part Five: Mission, Survival

Sadly, no photos me in that gray suit and red chicken-T-shirt survive. I wasn’t much for being photographed back then. For those of you who remember 2005, it was long before the heyday of selfies. Taking pictures with phones was not even a thing in 2000 when, suffering from the worst flu of my life, I stumbled into the student health center in Berkeley hoping to, at the very least, pass out somewhere help would be readily available. What does survive is me. Thanks to that vaccine, I only got one flu that year, not four or five. I got better, graduated, and went to Australia where I got to hold this cute koala, which was totally worth a shot in the arm, or 100, over a lifetime.

Getting the flu doesn’t make any aspect of your existence better. Not getting the flu might save your life. A shot in the arm is a very small price to pay to walk away from an event that might kill you. It’s pretty much that simple.

—

Your mission, should you choose to accept it: get vaccinated, punch flu in the face, and hug a koala.

Preferably, in that order.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2018-2020 Sheyna Gifford

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2018-2020 Sheyna Gifford- It very likely was my immune system punching that virus in the face that made me so sick. Like the 1918 flu, the 2000 flu set off cascades of immune responses that made those who got the flu super-duper sick from not only the flu but also their own body’s response to the flu. Isn’t immunology fun!

- Flu vaccines are effectively one-shot flu-Roombas. We build flu-Roombas every year based on the killer dust bunnies we see running around at the time. It takes us six months to build enough flu-Roombas to try to shield the world population. Unfortunately, by the time we set the flu-Roombas free, some of the killer dust bunnies have changed in size, shape, character, and hiding location. The flu-Roombas will sweep up the original set: that much is guaranteed. But as any Rooba-owner knows, no matter how good your robot, there will always be some bunnies left behind. How many bunnies the flu-Roombas miss, and how dynamite those killer rabbits are, defines the deadliness of every flu season.

- Yes we had Roombas in 2005. It wasn’t the dark ages, you know.

- Three, this year, that were running around 6-12 months ago

- There would still be issues of when to vaccinate people in a system like this. Those issues are solvable. We could vaccinate throughout the year. We could do it in a rolling fashion As needed, with multiple vaccines being given out during a particularly bad flu season. In any case, the issues of making and distributing a functional vaccine are much more daunting than how to give it out it’s made and delivered.